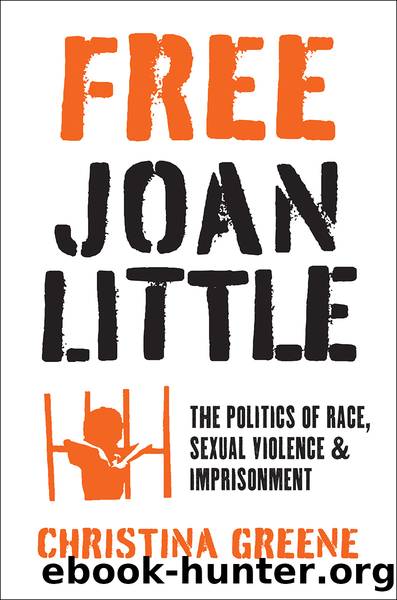

Free Joan Little by Christina Greene

Author:Christina Greene

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2022-09-18T00:00:00+00:00

Lillie Allen was the daughter of migrant farmworkers and had grown up in an all-Black community. Like Averyâs mother, Allen also attended Bethune-Cookman College in Florida. Although it was an-all Black campus, Allen was subjected to colorism and felt especially hurt by feeling excluded in a place âthat I thought was mine,â she said. Later she earned her masterâs in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Before joining the planning committee for the 1983 Black womenâs health conference, Allen had worked with teen pregnancy prevention programs in Atlantaâs public housing projects. She developed a program based on art, dialogue, and dance that used self-expression for young women to envision how their lives could be different. From those efforts and reevaluation counseling, which incorporated dialogue and active listening to work through difficult issues, Allen created the âBlack and Femaleâ self-help workshops. In addition to offering support to Black women unable to afford more traditional counseling or therapy, the workshops politicized self-help.18

Thus, the NBWHP did more than promote healing and instill self-empowerment in African American women. Like participants in feminist consciousness-raising sessions, both Allen and Avery understood that Black womenâs storytelling about traumas, like sexual abuse, was part of a process of political consciousness regarding gender oppression: âWhat we learn in the presence of other Black women, [is] that . . . we have an institution of sexism thatâs going on in our lives that tends to oppress us, and that the only way we can get out from under it is to learn to how to unhook.â Avery recalled the exhilaration of Black women who âtotally change their lives.â Sharing their stories, especially across generations and cultures, enabled women to place their experiences within a wider historical context that was culturally specific. For Avery, gathering cross-cultural experiences, especially the history of womenâs fertility control and antiviolence efforts, was crucial. âSometimes that will be what will give us our courage and give us our strength, because . . . these women ran into difficulties,â she said. The NBWHP newsletter, Vital Signs, not only provided health information but often carried political analyses, such as âThe Roots of Black Womenâs Oppression,â by Angela Davis, who was also a NBWHP board member. The NBWHP combined individual healing and empowerment with political education, thus bridging the separation between political action, educational projects, and service delivery.19

Many Black women activists were aware of their foremothersâ struggles and achievements and drew on them for inspiration. For Loretta Ross, Black womenâs history could shine a light on controversial issues like rape, contraception, and abortion. âI felt one of the ways to break through the silence was [to] show that there were other times in our history when we werenât so silent, when we were more active, when we were not as cowed by the political situation.â20 Avery was similarly inspired and frequently invoked Black womenâs history in her work with other women. She understood that her efforts were part of a distinctive ethic of care that had enabled African American women to survive and persevere from generation to generation.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4280)

Never by Ken Follett(3917)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3834)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3361)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3348)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3054)

Will by Will Smith(2890)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2339)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2316)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2309)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2288)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2210)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2207)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2177)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2177)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2103)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2079)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2043)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1996)